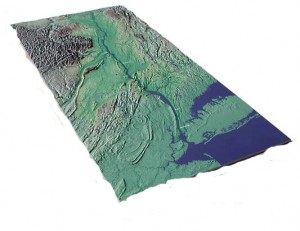

Transition NYC Bioregion

The New Economy and Local and Complementary Currencies

The New Economy is an emerging system of values, practices, institutions, policies and laws that support an economy designed to maximize current wellbeing and social justice without sacrificing the natural world or the resources available to future generations.

Those advocating a transition to a New Economy support an evolution where the priority is to sustain people and the planet; where social justice and cohesion are prized; and peace, communities, democracy and nature all flourish.

The New Economy is one in which real wealth – something that has intrinsic value – forms the basis for enterprises that provide for their employees, the community in which they are located, as well as making a profit for the owners. Local currencies are one tool by which communities can support a main street economy, assure that money stays in the community, and that local food and goods with intrinsic value are made and sold locally.

BerkShares, an Example of a Local Currency:

In an article by Bill Mckibben in Yes magazine in October of 2010 he describes how  BerkShares work, “You walk into any branch of the five banks that offer the notes and hand the teller $95 in U.S. dollars. She hands you 100 BerkShares. You spend them at the deli, the bar, or the bookstore. The bar owner then takes her BerkShares from the till and spends them at the deli, the bookstore, or, if she has to pay for something that nobody local is producing, she takes her BerkShares back to the bank and reconverts them into dollars.”

BerkShares work, “You walk into any branch of the five banks that offer the notes and hand the teller $95 in U.S. dollars. She hands you 100 BerkShares. You spend them at the deli, the bar, or the bookstore. The bar owner then takes her BerkShares from the till and spends them at the deli, the bookstore, or, if she has to pay for something that nobody local is producing, she takes her BerkShares back to the bank and reconverts them into dollars.”

BerskShares was originally a project of the E F Schumacher Society (Schumacher Center for a New Economics). BerkShares are a local currency for the Berkshire region of Massachusetts. BerkShares are a tool that enables merchants and consumers to plan for an alternative economic future. Plans include ATM’s, checking accounts, electronic transfers, and a loan program to make possible the creation of new, local businesses manufacturing more locally produced goods.

for an alternative economic future. Plans include ATM’s, checking accounts, electronic transfers, and a loan program to make possible the creation of new, local businesses manufacturing more locally produced goods.

Benefits of Local Currencies:

- Local currencies tend to circulate much more rapidly than national currencies. The same amount of currency is employed more times and results in far greater overall economic activity.

- Local currencies enable the community to utilize its existing productive resources that has a catalytic effect on the rest of the local economy.

- Since local currencies are only accepted within the community, their usage encourages the purchase of locally-produced and locally-available goods and services. Every dollar spent at a locally owned business generates two to four times more economic benefit than a dollar spent at a globally owned business.

- Growing evidence suggests that every dollar spent at a locally owned business generates two to four times more economic benefit – measured in income, wealth, jobs, and tax revenue – than a dollar spent at a globally owned business.

The Outlook for the New York Metropolitan Bioregion:

Wall Street and Main Street are names given to two economies with significantly different priorities and values that are often in competition. Wall Street is in the business of making  money to make money. Any involvement in the production of real goods and services is an incidental byproduct. Once a company, even one that started by making a useful product, begins to sell shares through exchanges or to private equity investors it becomes an agent of Wall Street. As a former executive of Odwalla told David Korten, “So long as we were privately owned by the founders, we were in the business of producing and marketing healthful fruit juice products. Once we went public, everything changed. From that event forward, we were in the business of making money.”

money to make money. Any involvement in the production of real goods and services is an incidental byproduct. Once a company, even one that started by making a useful product, begins to sell shares through exchanges or to private equity investors it becomes an agent of Wall Street. As a former executive of Odwalla told David Korten, “So long as we were privately owned by the founders, we were in the business of producing and marketing healthful fruit juice products. Once we went public, everything changed. From that event forward, we were in the business of making money.”

Creating this kind of entrepreneurship with “Main Street values” is much more difficult today. There is no easy way to start a new local business that creates real wealth and something with intrinsic value, in part because it is difficult for individuals to put money into worthy small businesses in need of capital. Our financial markets have evolved to serve big business even though small enterprises create three out of every four jobs and generate half of GDP. If you add in other “place based” nonprofits, co-ops, and the public sector, it is nearly 58 percent of all economic activity. Why then are we not investing some 58 percent of our retirement funds in Main Street enterprises?

worthy small businesses in need of capital. Our financial markets have evolved to serve big business even though small enterprises create three out of every four jobs and generate half of GDP. If you add in other “place based” nonprofits, co-ops, and the public sector, it is nearly 58 percent of all economic activity. Why then are we not investing some 58 percent of our retirement funds in Main Street enterprises?

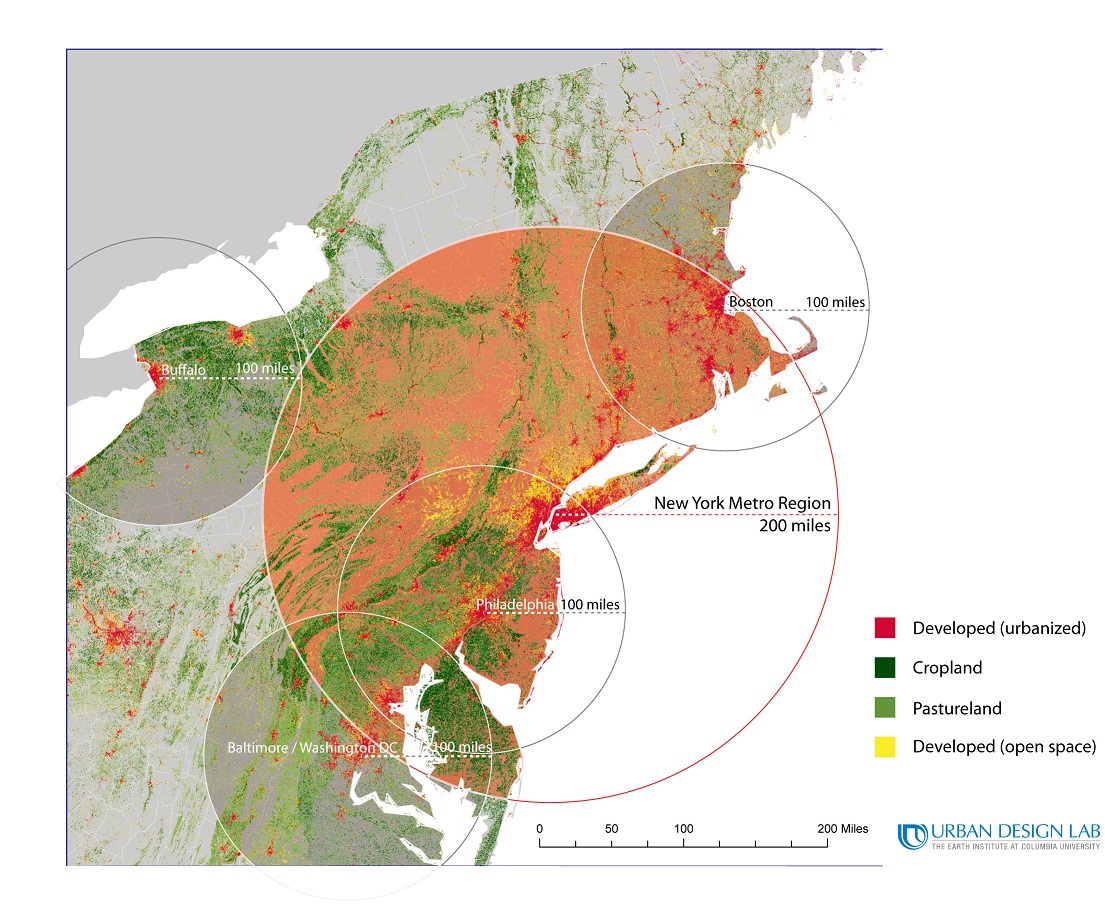

The New York Metropolitan bioregion needs new mechanisms, like local currencies to boost investment in local, place-based businesses. There is no easy way to start a new local business that creates real wealth and something with intrinsic value, in part because it is difficult for individuals to put capital into worthy small businesses. Our financial markets have evolved to serve big business even though small enterprises create three out of every four jobs and generate half of GDP. The result is that we who invest do so in Fortune 500 companies we distrust, and under-invest in the local businesses we know are essential for local vitality.

Amy Cortese, author of Locavesting, asks: If Americans have about $30 trillion invested, “imagine if half of that, $15 trillion, was invested in local communities rather than multinational conglomerates that are outsourcing jobs and not investing domestically. I think we’d be living in a far different world. (Even) One percent of $26 trillion is $260 billion  going to the Main Street economy and that’s a lot.….. (T)here is a very compelling case to be made for local investments as an asset class in a diversified portfolio.”

going to the Main Street economy and that’s a lot.….. (T)here is a very compelling case to be made for local investments as an asset class in a diversified portfolio.”

We urgently need to replace the current system with one that reasserts the right to a safe, healthy, productive environment for all; where “environment” is considered in its totality, inclusive of ecological, physical (natural and built); social, political, aesthetic, economic environments; and environmental justice. A community in which poverty and inequity are considered acceptable will always be prone to environmental and economic crises.

In “Thriving in the Age of Collapse,” Dymitry Orlov describes the predicament and options of typical Americans: A middle-aged couple with grown children are in for some bad  news; The first piece of bad news is that their retirement is going to be cancelled; Living out their “golden years” in a suburban house and continuing to drive will be impossible because of gas rationing and shortages. Their house will become too expensive to heat; Electricity will be cut off, then food may have to be provided by a some community-based service, and at some point when they can no longer stay in their home they may be evacuated to some hastily organized compound….

news; The first piece of bad news is that their retirement is going to be cancelled; Living out their “golden years” in a suburban house and continuing to drive will be impossible because of gas rationing and shortages. Their house will become too expensive to heat; Electricity will be cut off, then food may have to be provided by a some community-based service, and at some point when they can no longer stay in their home they may be evacuated to some hastily organized compound….

“Just when you are thinking Orlov is heartless in describing the futures of most of us hapless Americans, he switches to a brighter mode. (That middle aged couple) might very well rise to the occasion of the crisis, putting their career skills as a teachers to work in their community by creating a school, growing food, (or) negotiating a rainwater-capture system for their neighborhood….. Orlov’s faith in human resilience is variable, but present.” Andrae Collier, Grist Magazine, May 2010.

In a world of sprawling multinational conglomerates and complex securities disconnected from place and reality, there is something very simple and transparent about investing local currencies in a local company that you can see and touch and understand. As investing guru Peter Lynch has counseled, “It makes sense to invest in what you know.”

So we have choices to make as a community and a bio-region. Do we hope for “divine or alien” intervention, or do we start making our communities more resilient, invest in local businesses, and start local public banks and community based currencies?

There will be life after the age of “limitless growth,” and it will be a better life if our Bioregion’s priority is our people and the integrity of the biosphere, rather than high stock prices, corporate profits, and the reckless wasting of irreplaceable natural resources. It will be a challenging but exhilarating journey to develop and implement pragmatic positive change for the New York City Bioregion – to hospice the end of one era and midwife the beginning of another.

prices, corporate profits, and the reckless wasting of irreplaceable natural resources. It will be a challenging but exhilarating journey to develop and implement pragmatic positive change for the New York City Bioregion – to hospice the end of one era and midwife the beginning of another.