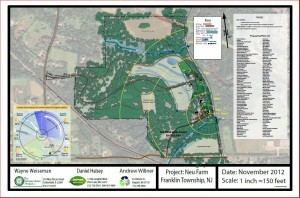

In 2012 Wayne Weiseman, Dan Halsey, and I were commissioned to do a Permaculture  Master Plan for the Neu Farm in Franklin Township, Hunterdon County, NJ. The farm is spectacular; it is 110 acres about 40 acres in fields and the balance in forest.

Master Plan for the Neu Farm in Franklin Township, Hunterdon County, NJ. The farm is spectacular; it is 110 acres about 40 acres in fields and the balance in forest.

There is a pre-revolutionary war stone farm house (that had one time been a tavern on the stage route to New Brunswick), a 19th century bank barn and several other beautiful

structures. The farm is bordered by the Capoolong Creek and transected by the Sydney Brook, two tributaries of the Raritan River. From top of the hill you can see the Delaware Water Gap.

structures. The farm is bordered by the Capoolong Creek and transected by the Sydney Brook, two tributaries of the Raritan River. From top of the hill you can see the Delaware Water Gap.

Beginning with an interview with Wendy Neu the following key words were generated for The Permaculture Master Plan:Vitality, Activity, Robust, Replenish, Farming, Forestry, Healthy, Exhilarating, Peaceful, Sanctuary, and Safe Place. Based on those key words the goal for agriculture (among several others) was developed.

- CSA

- Market Garden

- Bee Hives

- Placement: cropping areas

- Orchard

- Pasture

- Green House(s)

- Integrated Farming

- Fruits

- Herbs

- Nuts

- Kitchen Gardens

As we planned for the Neu Farm we took countless details into consideration. The farm is becoming a sanctuary and a small organic farming operation where people will also come to learn, where animals, plants and humans are in balance, and hands-on learning through direct experience will be implemented.Our plan was based in large part on the following:

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, we cannot sidestep the fact that we are witnessing chaotic changes in weather patterns across the country (and the world). Regardless of whether we can pinpoint the cause and affect weather-related events that are arriving at an ever-increasing rate, we need to do the right thing.

Three additional projects were anticipated in the Permaculture Plan; a flood plain and  stream corridor restoration project, a carriage horse sanctuary, and an experiential education program called Wellbeing Farm. (a more comprehensive version of Wellbeing Farm is a post on this blog)..

stream corridor restoration project, a carriage horse sanctuary, and an experiential education program called Wellbeing Farm. (a more comprehensive version of Wellbeing Farm is a post on this blog)..

One of the first projects undertaken was the rejuvenation of an existing orchard. There were several older pear trees still bearing but in need of  serious pruning and other care. About a ½ acre was fenced for deer protection and heirloom apples, stone fruit, and perennials like blueberries, persimmons, black raspberries, and kiwis were planted.

serious pruning and other care. About a ½ acre was fenced for deer protection and heirloom apples, stone fruit, and perennials like blueberries, persimmons, black raspberries, and kiwis were planted.

This past Fall, based in significant part on the expertise of organic orchardist Peter Tischler, we had an abundance of pears. Rather than letting them go to waste or  making a small amount of sauce or dried fruit as we did the year before, we decided to make pear hard cider also called Perry or Poire’. All cider is an alcoholic drink made from fermented crushed fruit, typically apples, primarily done to preserve the harvest (and calories)

making a small amount of sauce or dried fruit as we did the year before, we decided to make pear hard cider also called Perry or Poire’. All cider is an alcoholic drink made from fermented crushed fruit, typically apples, primarily done to preserve the harvest (and calories)

America’s love affair with hard cider stretches back to the first English settlers. Native trees were mostly crab apples so seeds and seedlings were imported from England. Grafting sweet apples to native trees started American cider production.With water quality

questionable, cider became the beverage of choice on the early American dinner table. Even children drank Ciderkin, a weaker alcoholic drink made from soaking apple pomace (the pulpy matter remaining after some other substance has been pressed or crushed) in water.By the

questionable, cider became the beverage of choice on the early American dinner table. Even children drank Ciderkin, a weaker alcoholic drink made from soaking apple pomace (the pulpy matter remaining after some other substance has been pressed or crushed) in water.By the  turn of the eighteenth Century, the average Massachusetts resident was consuming 35 gallons of cider a year. As the settlers began moving west, they brought along their love for cider.

turn of the eighteenth Century, the average Massachusetts resident was consuming 35 gallons of cider a year. As the settlers began moving west, they brought along their love for cider.

Many of us were taught about Johnny Appleseedwho turns out to be a real  person whose name was John Chapman and was a missionary for the Swedenborgian Church, who plantedand grafted small, fenced-in nurseries of cider apple trees throughout the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley.Some of those nineteenth centuryhomesteads still have a small cider orchard.

person whose name was John Chapman and was a missionary for the Swedenborgian Church, who plantedand grafted small, fenced-in nurseries of cider apple trees throughout the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley.Some of those nineteenth centuryhomesteads still have a small cider orchard.

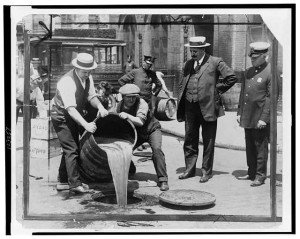

Cider started losing out to beer as the drink of choice during the early 1900’s. German and Eastern European immigrants brought preferred beer over cider, and the soil in the Midwest was more barley-friendly, so beer production was easier.However it was Prohibition and its restrictions on alcohol and the  Volstead Act limiting production of sweet cider to 200 gallons a year per orchard. Prohibitionists also burned countless fields of trees to the ground and surviving orchards began cultivating sweeter (non-cider) apples.

Volstead Act limiting production of sweet cider to 200 gallons a year per orchard. Prohibitionists also burned countless fields of trees to the ground and surviving orchards began cultivating sweeter (non-cider) apples.

Today cider making is on the rise in the US. While cheap apples are available in grocery stores from half way around the world, American orchardists have turned to cider to keep their farms profitable. More and more cider makers are showing up every year.

With hard cider making a comeback across the country, apple growers are tapping a new revenue stream by establishing farmstead cideries and planting varieties too tart or tannic for eating but perfect for smashing and fermenting into alcoholic cider.

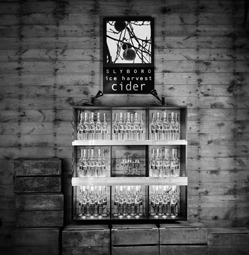

“We’re planting a lot of new trees so we can meet the demand for cider,” said Dan Wilson, owner of Hicks Orchard and Slyboro Ciderhouse on the Vermont border in Granville. “This year we planted 2,000 cider varieties and next year we’ll plant 2,500 in high-density orchards.”

Slyboro is among 10 craft producers who banded together to form the Hudson Valley Cider Alliance to establish hard cider and apple spirits as signature products of the region.Doc’s Draft Hard Ciders, one of the few making a pear cider in Warwick, NY.

Slyboro is among 10 craft producers who banded together to form the Hudson Valley Cider Alliance to establish hard cider and apple spirits as signature products of the region.Doc’s Draft Hard Ciders, one of the few making a pear cider in Warwick, NY.

Peter is planting a cider orchard at New Ark Farms in north-west NJ. New Jersey is also home to nearly 60 registered orchards and boasts one award winning apple wine producer and a new cider producer. Twisted Limb is a cidery producing alcoholic cider near Newton NJ. As of October 16, 2014 there was cidery and meadery licensing bill before the NJ Legislature. That says in part:

“In New Jersey, we’ve done a great deal of legislation to encourage our New Jersey-based wineries and craft breweries, which has created jobs and economic stimulus for our region,” said Lampitt. “This bill builds on that momentum by updating outdated laws. By providing support to cideries and meaderies in New Jersey, we are taking the next step in helping our homegrown industries thrive.” “As the Garden State, New Jersey should be leading the way when it comes to developing products from fruit and honey, not getting left  behind by our draconian liquor laws,” said Senator Norcross. “We have proven time and again that craft products from this state are in high demand. Let’s capitalize on our rich agriculture industry and spur economic growth in the process.” Bill S2461/A3740 creates a cidery and meadery license which permits the holder to manufacture a maximum of 25,000 barrels of hard cider and 25,000 barrels of mead and to sell these products to wholesalers and retailers in New Jersey and other states.”

behind by our draconian liquor laws,” said Senator Norcross. “We have proven time and again that craft products from this state are in high demand. Let’s capitalize on our rich agriculture industry and spur economic growth in the process.” Bill S2461/A3740 creates a cidery and meadery license which permits the holder to manufacture a maximum of 25,000 barrels of hard cider and 25,000 barrels of mead and to sell these products to wholesalers and retailers in New Jersey and other states.”

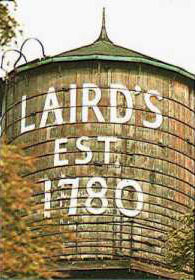

New Jersey is also home to the Laird & Company that has been making Apple-Jack since 1780 in Colts Neck/Scobeyville, NJ. Although I knew this distillery was somewhere in Monmouth County, it wasn’t until last Fall that I discovered it by accident while getting  some apples from a u-pick orchard just across the road from the old homestead and distillery. It occurred to me that some of the trees I was picking from might be descendants of the trees that the apples for the first batch of apple-jack were picked. I stopped at a liquor store on the way home and bought a bottle. That cool evening in front of the stove I enjoyed a sweet cider, “fire-cider,” (our bottle came down the Hudson on Ceres, the Vermont Sail Freight sailing barge) and Laird’s Apple-Jack cocktail – refreshing and delicious.

some apples from a u-pick orchard just across the road from the old homestead and distillery. It occurred to me that some of the trees I was picking from might be descendants of the trees that the apples for the first batch of apple-jack were picked. I stopped at a liquor store on the way home and bought a bottle. That cool evening in front of the stove I enjoyed a sweet cider, “fire-cider,” (our bottle came down the Hudson on Ceres, the Vermont Sail Freight sailing barge) and Laird’s Apple-Jack cocktail – refreshing and delicious.

“For almost 300 years, the art of producing Apple-Jack has been passed down through generation of the Laird Family. Laird was America’s first commercial distillery with License #1. “

That said we didn’t have apples but pears. So we decided to make Perry or Poire’. Perry is similar to apple cider but is made from pear juice instead of apples. It is usually smoother, slightly sweeter, less sharp in flavor than apple cider. Like apple cider there are steps to production.

- Harvest and store the pears until ripe

- Pulping and pressing the pears

- Fermenting the juice

- And bottling the Perry.

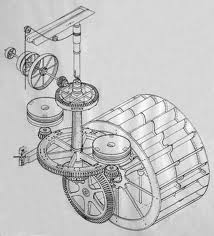

Once the pears were ripe we needed a cider press. I first looked for a used one but no luck, so I bought a new one from Pleasant Hill Grain . In the meantime Peter had picked 30+ bushels of pears and was waiting for them to ripen enough to be able to crush the fruit.

Once the fruit was ripe three of us, Peter, Dennis Fabis, and I manually crushed the pears IMG_1800 and then put them through the press. There was a lot of juice (delicious right from the press), about gallon a bushel  . The juice was stored in clean pails. At the end of the day there was a lot of pulp for feeding to local pigs, a lot of sticky equipment to clean, and a lot of cider alchemy going on to begin the fermentation process. Hard work but the reward was a gallon of fresh juice for all of us to take home, and ultimately the equivalent of two hundred beer bottle sized portions of hard pear cider that we decided to call Johnny’s Hard Cider with a nod to John Neu.

. The juice was stored in clean pails. At the end of the day there was a lot of pulp for feeding to local pigs, a lot of sticky equipment to clean, and a lot of cider alchemy going on to begin the fermentation process. Hard work but the reward was a gallon of fresh juice for all of us to take home, and ultimately the equivalent of two hundred beer bottle sized portions of hard pear cider that we decided to call Johnny’s Hard Cider with a nod to John Neu.

Fermentation began after Peter added wine maker’s yeast and some brown sugar for an extra kick, little bit of tannin for sharpness, wine makers acid blend, and raisins for body. The juice was left in open  fermentation For the next week the cider was really active, you could see surface churning from all the CO2 being generated. When the fermentation started to slow, the buckets were racked into 5 gallon glass carboys with a bubbler on top to let some gas escape and prevent the cider from turning into vinegar. In early December the cider was racked to get the sediment out, into clean carboys. Peter also tested the

fermentation For the next week the cider was really active, you could see surface churning from all the CO2 being generated. When the fermentation started to slow, the buckets were racked into 5 gallon glass carboys with a bubbler on top to let some gas escape and prevent the cider from turning into vinegar. In early December the cider was racked to get the sediment out, into clean carboys. Peter also tested the  alcohol levels of the cider it was pretty good. It also tasted great (it will eventually be 6-7% alcohol). In early Spring the cider will be racked into bottles and kegs to increase the carbonation. Peter’s advice to me was to “drink a lot of beer this winter and save the bottles.”

alcohol levels of the cider it was pretty good. It also tasted great (it will eventually be 6-7% alcohol). In early Spring the cider will be racked into bottles and kegs to increase the carbonation. Peter’s advice to me was to “drink a lot of beer this winter and save the bottles.”

This experiment may lead to a full scale cidery at the Neu farm and perhaps a tasting room in the basement of the stone farm house that was once a tavern..